NO&T IP Law Update

Since the introduction of Article 68-2 of the Patent Act of Japan in 1987, the scope of a patentee’s patent rights during the patent’s extended term has been a matter of unclarity and dispute. On May 15, 2025, the Tokyo District Court (the “Court”) addressed this issue in Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Bristol-Myers Squibb, a case involving a claim asserted by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (“BMS”) against Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (“Sawai”) alleging that a generic drug sold by Sawai infringed a patent owned by BMS during the patent’s extended term. Based on various findings of fact, the Court ruled against BMS’s claim and determined that Sawai’s product did not infringe BMS’s patent.

The Court noted that there were material differences between BMS’s drug—which served as the basis for the patent term extension—and Sawai’s drug, both in terms of each drug’s active ingredient and inactive ingredients (or excipients). It examined the reasons behind Sawai’s selection of different excipients and found that these choices were not based on well-known or conventional techniques, but rather on Sawai’s own proprietary methods. Accordingly, the Court concluded that the scope of BMS’s patent during its extended term did not extend to cover Sawai’s product and thus ruled against BMS’s infringement claim.

This newsletter provides an overview of the Tokyo District Court’s judgment in Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Bristol-Myers Squibb along with our commentary on this topic.

Under Article 67(1) of the Patent Act of Japan, the term of a patent expires 20 years after the filing date of the patent application.

However, a patent term extension (PTE) (i.e., an extension of the term of a patent beyond the standard duration) may be granted when a marketing authorization is required to implement the patented medicinal invention (Articles 67(4) and 67-7(a) of the Patent Act). The PTE is intended to restore to the patent term the period during which the patented invention could not be implemented due to the necessity of obtaining marketing authorization.

When multiple marketing authorizations are issued in relation to a single patent, PTEs may be granted based on each of those authorizations (Patent and Utility Model Examination Guidelines, Part IX, Chapter 2, Section 3.1.1(3)) and the exclusive patent right of the patentee will be extended accordingly.

When a PTE is granted, the scope of the patent during the extended term is limited to the drug that was the subject of the marketing authorization on which the PTE was based, and only for the use specified in that authorization (Article 68-2 of the Patent Act).

This means that, in order to exercise rights under a patent during its extended term, the patentee must prove that (i) the alleged infringing drug falls within the technical scope of the patented invention, (ii) the alleged infringing drug is the same as the drug that was the subject of the marketing authorization on which the PTE was based, and (iii) the alleged infringing drug is used for the use specified in that authorization.

In 1987, when Article 68-2 was introduced, the Japan Patent Office (JPO) explained that the scope of the patent during the extended term under Article 68-2 is limited to the patentee’s exclusive rights in relation to any drug having the same active ingredient for the same indication and usage as the drug that is the subject of the marketing authorization on which the PTE was based.

However, on May 29, 2009, the Intellectual Property High Court (IPHC), in Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. JPO, rejected this interpretation by the JPO. Although the IPHC’s judgment was not rendered in a patent infringement action but rather in an appeal against the JPO’s trial decision denying a PTE—and its statement on the interpretation of Article 68-2 is considered obiter dictum (i.e., a remark by a court in a legal opinion about a point of law which is said in passing and does not form part of the decision of the case)—the IPHC stated the following: when a patented invention relates to pharmaceuticals, among the embodiments falling within the technical scope of the patented invention, the patent during the extended term covers only the implementation of the patented invention with respect to “products” specified by the “ingredients,” “quantities,” and “structure” of the drug that was the subject of the marketing authorization, and with respect to “products” defined by the “use” of such drug (including equivalents and products considered substantially identical).

On January 20, 2017, the IPHC addressed the interpretation of Article 68-2 for the first time in a patent infringement case, in Debiopharm International SA v. Towa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The IPHC held that the effect of the patent during the extended term covers not only a “product” (drug) specified by the “ingredients, quantity, dosage, administration, indication, and usage” stipulated in the marketing authorization, but also those considered substantially identical as pharmaceuticals. Even when the allegedly infringing drug differs from the configuration set out in the marketing authorization, if such differences are merely minor or insignificant as a whole, the allegedly infringing drug is considered substantially identical to the drug subject to the marketing authorization and falls within the scope of the patent during its extended term.

In Debiopharm, the IPHC further identified four categories of drugs that may be considered “substantially identical.” Among them, the first category refers to cases in which the patented invention is characterized solely by the active ingredient of a drug, and where some inactive ingredients are added or modified using techniques that were well-known and conventional at the time of the marketing authorization application.

It should be noted that in Debiopharm, the IPHC ultimately held that the allegedly infringing drug did not fall within the technical scope of the patented invention, without even considering the limitation under Article 68-2. Therefore, the court’s statements regarding Article 68-2 in Debiopharm should still be regarded as obiter dicta.

Thus, prior to the Tokyo District Court’s judgment on May 15, 2025, there had been no judicial precedent addressing the interpretation of Article 68-2 in a case where the court determines that, or the alleged infringer admits that, an allegedly infringing drug fell within the technical scope of a patent for which a PTE was granted.

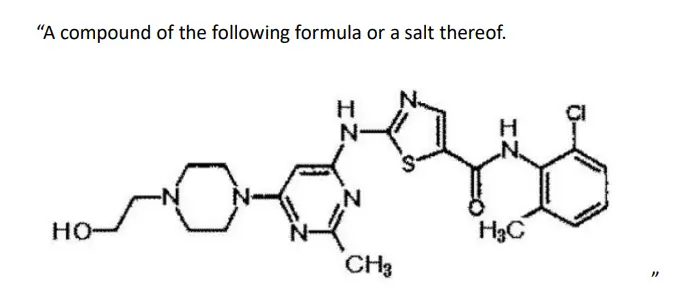

BMS is the patentee of Japan Patent No. 3,989,175, entitled “Cyclic Protein Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors” (the “Patent”). The filing date of the Patent is April 12, 2000. Claim 9 of the Patent reads as follows:

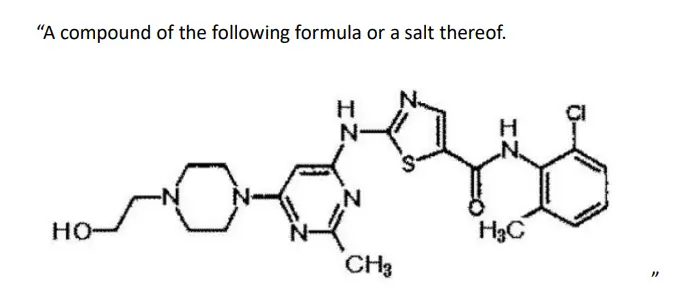

PTEs for the Patent were granted for a period of 1 year, 5 months, and 24 days based on the marketing authorizations for “Sprycel® Tablets 20mg” and “Sprycel® Tablets 50mg” (collectively, “Sprycel® Tablets”), respectively. The generic name of Sprycel® Tablets is dasatinib hydrate.

Additional PTEs for the Patent were granted for a period of 3 years, 9 months, and 15 days based on the partial change approvals of the marketing authorization for Sprycel® Tablets.

Sawai obtained marketing authorization for a generic version of Sprycel® Tablets (“Sawai’s Product”) on February 15, 2022, and began sales on June 17, 2022. On October 4, 2023, Sawai obtained partial change approval of the marketing authorization for Sawai’s Product to add “chronic myeloid leukemia” to its indication and usage. Accordingly, Sawai updated the description in the package insert and began marketing Sawai’s Product with indication and usage for chronic myeloid leukemia.

Sawai filed a lawsuit against BMS seeking a declaratory judgment determining that BMS does not have a right to seek an injunction against Sawai in relation to Sawai’s Product or a right to seek compensation for damages allegedly caused by Sawai’s patent infringement, arguing that the scope of the Patent during its extended term does not cover Sawai’s Products and thus there is no basis for an injunction or for an award of damages as there is no patent infringement.

In response, BMS filed a counterclaim against Sawai seeking compensation for damages allegedly caused by Sawai’s patent infringement, arguing that Sawai’s Product falls within the technical scope of the invention recited in Claim 9 of the Patent (the “Invention”) and that the scope of the Patent during its extended term covers Sawai’s Product, and thus an award of damages is proper based on the patent infringement.

There was no dispute between the parties as to the fact that Sawai’s Product comprises a compound falling within the technical scope of the Invention. Therefore, the key issue in dispute was whether the scope of the Patent during its extended term covers Sawai’s Product.

The Tokyo District Court in Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Bristol-Myers Squibb determined that the scope of the Patent during its extended term did not cover Sawai’s Product and denied BMS’s claim.

The Tokyo District Court interpreted Article 68-2 of the Patent Act generally in the same manner as the IPHC’s interpretation in Debiopharm. The Court stated that the scope of a patent during its extended term covers not only the “product” (drug) specified by the “ingredients, quantity, dosage, administration, indication and usage” stipulated in the marketing authorization, but also those that are substantially identical to it as pharmaceuticals.

The Court further stated that even when the allegedly infringing drug differs from the configuration set out in the marketing authorization, if such differences are merely minor or insignificant as a whole, the allegedly infringing drug is considered substantially identical to the drug subject to the marketing authorization and falls within the scope of the patent during its extended term.

The Court further ruled that, in cases where the patent invention is characterized solely by the active ingredient of a drug, and where some inactive ingredients are added or modified using techniques that were well-known and conventional at the time of the marketing authorization application, such differences are regarded as “minor or insignificant as a whole.” Accordingly, the allegedly infringing drug is considered to be substantially identical to the drug subject to the marketing authorization as a pharmaceutical.

In summary, the Court made the following findings of facts:

The Court also made detailed findings on various tests conducted by Sawai. Based on those findings, the Court further found that:

Consequently, the Court found that Sawai’s Product involved the addition and modification of excipients to address challenges arising from differences in the active ingredients between Sprycel® Tablets (dasatinib hydrate) and Sawai’s Product (dasatinib anhydride).

The Court further determined that there was no adequate evidence to recognize that such addition and modification of excipients were based on well-known or conventional techniques. Rather, the Court found that these additions and modifications were made by Sawai based on its own techniques. Accordingly, the Court concluded that Sawai’s Product cannot be considered substantially identical to Sprycel® Tablets as a pharmaceutical.

As a side note, the court did not base its determination—that Sawai’s product is not substantially identical to Sprycel® Tablets—on the difference in active ingredients (dasatinib hydrate versus dasatinib anhydride).

The law concerning the scope of a patent during its extended term continues to evolve. To the best of our knowledge, the Tokyo District Court’s judgment in Sawai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Bristol-Myers Squibb is the first court decision to directly address the interpretation and application of Article 68-2 as the central issue in a case where the court determines that, or the alleged infringer admits that, the allegedly infringing product falls within the technical scope of a patent for which a PTE was granted.

From this perspective, the Tokyo District Court’s judgment in this case is highly significant. Although it is a decision by a court of first instance, if upheld by the appellate courts, it would suggest that the enforceability of patents during their extended terms is considerably limited—as anticipated following the IPHC’s interpretation of Article 68-2 in Debiopharm International SA v. Towa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

We will continue to monitor developments in this area, including any future court decisions addressing the same issue, and will keep you informed.

This newsletter is given as general information for reference purposes only and therefore does not constitute our firm’s legal advice. Any opinion stated in this newsletter is a personal view of the author(s) and not our firm’s official view. For any specific matter or legal issue, please do not rely on this newsletter but make sure to consult a legal adviser. We would be delighted to answer your questions, if any.

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Claire Chong, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahito Hirayama (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

(June 2025)

Shin Koike

Kenji Tosaki, Takahito Hirayama (Co-author)