NO&T IP Law Update

Generative artificial intelligence (generative AI) has captured the attention of the world. We have recently seen the launch of a wide variety of generative AI services, some of which have even become familiar in our daily lives and at work. For example, a new image or portrait can be easily generated by using services such as “Stable Diffusion” or “Imagen”. Also, “Chat GPT” (Chat Generative Pre-training Transformer), which has already had an enormous impact, enables us to obtain response to almost any question posed to an artificial intelligence in natural language.

In tandem with the development of these generative AI services and technologies, there has been worldwide discussion about various related legal issues. Japan has had its own lively discussions on the subject, including consideration of the relation between generative AI and copyright law.

In light of Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act of Japan, Japan is sometimes described as a “Machine Learning Paradise”. But can the same Article support the description of Japan as a “Generative AI Paradise”?

Copyright infringement in relation to generative AI may take place in two situations because acts of exploitation defined in the Copyright Act may take place in the two situations. One is when developing generative AI. In making generative AI learn a work, datasets for training are created and the datasets are input into a training program. Acts of reproduction of copyrighted work, which are designated as acts of exploitation in the Copyright Act, are likely to take place in these processes. The other is when using generative AI. In generating works by using generative AI, acts of reproduction, acts of adaptation and/or acts of public transmission of copyrighted work, which are designated as acts of exploitation in the Copyright Act, may take place. For this reason, we would like to explain (x) whether acts of exploitation when developing generative AI constitute copyright infringement in Part II. below, and (y) whether acts in the course of producing works by using a generative AI fall under acts of exploitation of existing copyrighted works in Part III. below.

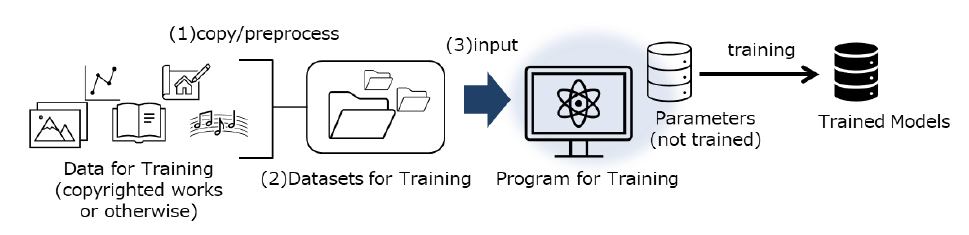

When developing generative AI, generative AI developers (1) copy, collect and preprocess large amounts of copyright-protected and non-copyright-protected data, (2) create datasets for training, and (3) input these datasets into a training program (See, Fig. 1 below). In the course of the processes (1) and (2) above, it is likely that acts of reproduction of copyrighted works take place. An issue that presents itself at this stage is whether the acts of reproduction of a copyrighted work for use in generative AI development constitutes copyright infringement of such work.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Under the Copyright Act, an act of making a given work that is identical or similar to an existing copyrighted work in terms of original expression in reliance on the said existing copyrighted work is considered to fall under “reproduction” under the Copyright Act and therefore, constitutes, in principle, copyright infringement. When developing generative AI, the data from a large volume of copyrighted work is duplicated for use in such development and it is considered that an act of such duplication falls under “reproduction” under the Copyright Act. The key question concerning copyright infringement at this stage becomes whether Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act applies.

In light of the above, it is necessary to consider the applicability of Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act, which is just the article that caused Japan to be described as a “Machine Learning Paradise.”

Under this Article, a work may be exploited in any way and to the extent considered necessary, (I) in cases in which it is not a person’s purpose to personally enjoy or cause another person to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in that work. However, this exception does not apply (II) if the action would unreasonably prejudice the interests of the copyright owner in light of the nature or purpose of the work or the circumstances of its exploitation. Please be advised that Article 30-4 lists three examples of cases in which it is not a person’s purpose to personally enjoy or cause another person to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in a given work, one of which is the exploitation of a work for use in data analysis (meaning the extraction, comparison, classification, or other statistical analysis of the constituent language, sounds, images, or other elemental data from a large number of works or a large volume of other such data).

In determining whether Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act applies, the most important considerations are (1) whether, as set out in (I) above, the purpose of the exploitation of a work is “to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in that work” (hereinafter referred to as the “Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement”) and, (2) if the answer to (1) is negative, whether such exploitation falls under (II) above, concerning unreasonable prejudice to the interests of the copyright owner.

Whether the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement is satisfied is determined with regard to whether the exploitation of the copyrighted work at issue has, as its intent, the satisfaction of one’s intellectual desire or spiritual needs, through an action such as viewing. The following three examples illustrate the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement.

Example 1: A person collects and preprocesses various copyrighted landscape pictures (including copying these pictures) for the purpose of developing AI for creating 3D CGI movies, which movies have the “essential features of expression” of such copyrighted works.※1

In this case, it is highly likely that a Japanese court would determine that the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement has NOT been satisfied, and that a copyright infringement has been established. This is because, while the purpose of the developer in this example is to use files containing these pictures for the purpose of data analysis (i.e., machine learning to develop AI), the developer also intends to create 3D CGI movies, and to watch these movies or show them to other humans. The court thus would be highly likely to find that this intent constitutes the purpose to personally enjoy or cause another person to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in those works.

Example 2: A person uses copyrighted works (e.g., pictures, music, and literary works) only for training a generative AI, and configures this generative AI only to produce works that are not identical or similar to any copyrighted elements of such copyrighted works.

While this hypothetical is a bit less certain than the previous, it is more likely than not that the court would determine that the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement is satisfied, although we do not know if one can configure a generative AI only to produce works that are not identical or similar to any copyrighted work that the AI learned in terms of original expression. This is because in this case, the works that the generative AI produce do not have the “essential features of expression” of the copyrighted works that the AI learned and one cannot enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in the copyrighted works which he uses for AI training.

Example 3: A person copies copyrighted works (e.g., pictures, music, and literary works) in order to create datasets to be used in the development of AI, after which he sells these datasets to third parties. He does not carry out this activity with the purpose of allowing others to use these datasets for the development of generative AI which will generate thoughts or sentiments expressed in the copyrighted works.※2

In this case, the purpose of the dataset creator is not to enjoy thoughts or sentiments expressed in the collected copyrighted works, but only to profit by selling datasets built on data analysis thereof. However, unless the dataset creator confirms that the third party’s purpose is a non-enjoyment purpose, the court will likely find that the dataset creator’s purpose includes a purpose to cause another person to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in a work. Therefore, if (i) each of the third party discloses his/her specific non-enjoyment purpose of using the dataset to the dataset creator, (ii) there are reasonable grounds for the dataset creator to believe that each of the third party’s purpose is non-enjoyment purpose and (iii) all the third parties, users of the datasets, also specifically agree with using the datasets only for the specifically described non-enjoyment purpose and not transferring the datasets to others, it is likely that the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement is satisfied in this case, irrespective of his purpose for gaining profits.

Please be advised that, even where the main purpose of using copyrighted work is not enjoyment, if enjoyment is found to be a subsidiary purpose in the use thereof, such use does NOT satisfy the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement.

Based on the foregoing, the use of data from copyrighted work for developing generative AI causes the probability of not being found that the person does not have a purpose to enjoy or cause another person to enjoy the thoughts or sentiments expressed in the copyrighted work, as in Example 1. It is important to carefully consider whether or not the exploitation of the copyrighted work at issue actually satisfies the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement in developing generative AI.

The following factors should be considered in determining whether the exploitation of copyrighted work has the effect of “unreasonable prejudice to the interests of the copyright owner,” in which case such exploitation would constitute copyright infringement regardless of whether the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement is met:

For example, where a person copies an AI training dataset available on a market, conducts data analysis of this dataset as a whole, and uses this data analysis to sell a competing AI training dataset※3, this interference with the existing market could likely constitute unreasonable prejudice to the interests of the copyright owner.

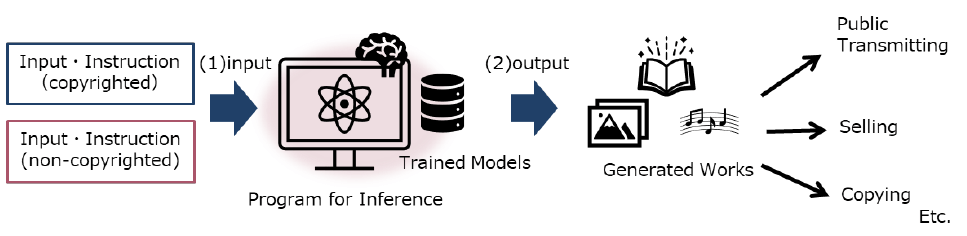

When generating a work by using a generative AI, the generated work may be identical or similar to the existing copyrighted work that was included in the dataset used for the development of the AI, or to the existing copyrighted work that was included in the instruction by the user (See, Fig. 2 below). A copyright infringement issue that presents itself at this stage is whether (1) the copying and saving an existing copyrighted work on a server when such work is input into the AI by the user as part of the instruction to the AI, and (2) the sale, copying or public transmission of the work generated by the AI constitute copyright infringement.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

As noted above, an act of making a given work that is identical or similar to an existing copyrighted work in terms of original expression in reliance on the said existing copyrighted work (the “Reliance”) is considered to fall under “reproduction” under the Copyright Act and therefore, constitutes, in principle, copyright infringement. With respect to “adaptation” and “making a transmission to the public” under the Copyright Act as well, an act of exploitation of the given work in reliance on the existing copyrighted work (the Reliance) is also required.

With respect to the Reliance, some argue that the Reliance can be established when the producer of a new work already had knowledge of an existing copyrighted work and made use of such copyrighted work, e.g., the form of expression thereof in the creation of the new work. Some argue that the reliance is found when a person who produced a new work had recognized the content of the expression in the existing copyrighted work and had an intent to make use of it in the new work. Whether a new work is produced in reliance on an existing copyrighted work is generally determined by examining (a) whether the producer had knowledge of the existence and the content of the existing copyrighted work, or had a reasonable opportunity to access the existing copyrighted work, (b) the extent of identity between the existing copyrighted work and the new work, including deliberate errors and shared mistakes. However, as the users of generative AI will not likely know specifically which copyrighted works were included in the dataset used to train a given AI, this conventional reliance standard may not be a good fit when it comes to works produced by generative AI. Some argue that, as long as the existing copyrighted work was included in the dataset, the user of the generative AI is deemed to have had access to the existing copyrighted work and therefore should be found to have relied upon same. Some argue that the reliance should not be found in the case where the existing copyrighted work was fragmented into parameters in the training process because in this case the expression of the work is not really used. In any event, it is highly likely that a court will find copyright infringement where existing copyrighted work was included in the dataset used to train generative AI. It should be noted that further discussion between the government, practitioners and scholars is expected with respect to this issue.

Whether a produced work is identical or similar to the copyrighted work is determined with reference to the same criteria by which a court determines whether, in a non-AI generated work, such work shares the same “essential features of expression” as the copyrighted work.

As a side note, Article 30-4 of the Copyright Act does not apply to the production of a new work by using generative AI because it is obvious that the production of a new work does not meet the Non-Enjoyment Purpose Requirement.

On the basis of the foregoing, the copying, sale or public transmission of a work that shares the same “essential features of expression” as an existing copyrighted work produced via generative AI that learned the dataset including the existing copyrighted work is likely to fall under “reproduction,” “adaptation” or “making a transmission to the public” under the Copyright Act and therefore constitute copyright infringement. Therefore, when making generative AI produce a new work, it would be advisable to check with the developer of the generative AI if any copyrighted work is included in the dataset, and if the answer is yes, check with the developer if licenses are obtained from the copyright holder, or if there is any other legal reason to prevent copyright infringement (e.g., the expiry of the copyright term).

Generative AI technology is advancing daily, and, along with this advance, generative AI is becoming more and more important in the business world. Under the current copyright law, both (i) use of an existing copyrighted work as data to be input into a training program of a generative AI to produce a new work and (ii) producing a new work that shares the same “essential features of expression” as an existing copyrighted work by using a generative AI are likely to constitute copyright infringement. It should be noted that the law may change in the future in accordance with further discussion between the government, practitioners and scholars. We will follow the discussion and keep you updated.

*1

See, Copyright Division, Agency of Cultural Affairs “AI to Chosakuken no Kankeitou ni tsuite” (Relationship between AI and copyrights, etc.).

*2

This example is referred to in Copyright Division, Agency of Cultural Affairs “Chosakuken no ichibu wo kaiseisuru houritsu (Heisei 30-nen kaisei) ni tsuite” (Explanation regarding the act to amend a part of the Copyright Act of Japan in 2018), Copyright no. 692 vol. 58, p. 35.

*3

This example is also referred to in Copyright Division, Agency of Cultural Affairs “AI to Chosakuken” (AI and Copyright), p.39.

This newsletter is given as general information for reference purposes only and therefore does not constitute our firm’s legal advice. Any opinion stated in this newsletter is a personal view of the author(s) and not our firm’s official view. For any specific matter or legal issue, please do not rely on this newsletter but make sure to consult a legal adviser. We would be delighted to answer your questions, if any.

(June 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yukiko Konno, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author), Masahiro Kondo (Contributor)

(April 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Akira Komatsu (Co-author)

(April 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Shu Sasaki, Kazuyuki Ohno, Otoki Shimizu (Co-author)

Poonyisa Sornchangwat, Kwanchanok Jantakram (Co-author)

(June 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yukiko Konno, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author), Masahiro Kondo (Contributor)

(April 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Akira Komatsu (Co-author)

Patricia O. Ko

(February 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Akira Komatsu, Yuki Matsumiya (Co-author)

(June 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yukiko Konno, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author), Masahiro Kondo (Contributor)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahito Hirayama (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(April 2025)

Shiro Kato, Chihiro Shimaoka (Co-author)

(May 2025)

Yoshimi Ohara, Shota Toda, Annia Hsu (Co-author)

Patricia O. Ko

Hiroki Tajima

Kenji Tosaki, Takahito Hirayama (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahito Hirayama (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Masato Kumeuchi, Soichiro Unami (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(June 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yukiko Konno, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author), Masahiro Kondo (Contributor)

(April 2025)

Shiro Kato, Chihiro Shimaoka (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Masato Kumeuchi, Soichiro Unami (Co-author)

(March 2025)

Kenji Tosaki, Masanori Tosu (Co-author)