NO&T IP Law Update

The Supreme Court of Japan rendered two unprecedented judgments on March 3, 2025, addressing the application of the principle of territoriality of patents to cross-border activities. In short, the Supreme Court ruled for the first time in its history that cross-border activities, including the use of servers located outside Japan, can constitute the “implementation” of a patented invention and therefore an infringement of a Japanese patent right.

In this newsletter, we explain these judgments and provide our summary commentary on them.

The “principle of territoriality of patents” is a fundamental concept under Japanese patent law, even though there is no provision in the Patent Act of Japan expressly addressing it. Under Japanese patent law, the principle provides that a patent right is effective only within the territory of the country of the government which granted the patent (e.g., a patent right granted by the Government of Japan is only effective within the territory of Japan).

However, the rapid and expansive development of information and network technology in recent times has enabled all manner of tangible and intangible objects to instantaneously connect beyond the physical borders of nations. In this context, the application of the principle of territoriality of patents to cross-border activities has become extremely troublesome for holders of Japanese patents and their legal counsel trying to protect their patents.

If the principle of territoriality is rigidly applied, a Japanese patent right can only be infringed when all of the constituent elements of the patented invention are present within the territory of Japan. This results in easy circumvention of infringement of Japanese patent rights simply by using servers located outside Japan, especially in the case of IT-network-related inventions.

The two judgments rendered by the Supreme Court on March 3, 2025, were for two cases between the same parties. For ease of understanding, the first case is hereinafter referred to as “Dwango I” and the second case is hereinafter referred to as “Dwango II”.

The plaintiff, Dwango Co., Ltd. (“Dwango”), a Japanese corporation, owned Japanese Patent No. 4734471 (“’471 Patent”) pertaining to the invention of a computer program (the “Program Invention”) and that of a display device (the “Display Device Invention”).※1 The defendant, FC2, Inc. (“FC2”), a U.S. company, operated a business which provided three types of online video-streaming-with-comments services (the “Services”) jointly with another defendant, Homepage System, Inc. (“HPS”), a Japanese corporation.

Dwango essentially made two main claims in this case. First, Dwango claimed that:

Second, Dwango further claimed that:

Based on these claims, in 2016, Dwango commenced litigation against FC2 and HPS in the Tokyo District Court seeking an injunction to prevent the Distribution of the Programs and an award for compensatory damages.

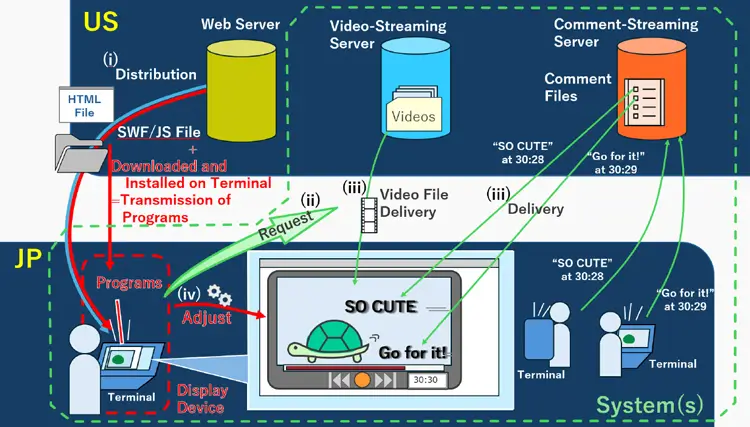

The Services enabled users to add comments while watching videos, and when a user played a video, comments added by other users are displayed moving from right to left on the video being played, synchronized with the timing of when the comments were added.※3

<Figure: Structure of the Services>

The Programs function so that videos are played with comments in accordance with the files distributed, downloaded and installed in (i) in the above figure.

The key issues in Dwango I were:

On September 19, 2018, the Tokyo District Court dismissed both claims of Dwango holding that the Programs did not fall within the scope of the Program Inventions.

Dwango next appealed to the Intellectual Property High Court of Japan (the “IPHC”). On July 20, 2022, the IPHC allowed a part of the claims of Dwango finding that the defendants had infringed the ’471 Patent.※4 In response, FC2 and HPS filed petitions to the Supreme Court for final appeal challenging the ruling of the IPHC.

On March 3, 2025, the Supreme Court dismissed the final appeal made by FC2 and HPS, which resulted in the judgment of the IPHC being affirmed as the correct and final binding decision (the “Supreme Court Dwango I Judgment”).

The Supreme Court, referring to the principle of territoriality, stated that a Japanese patent right is effective only within the territory of Japan. However, the Supreme Court went further and acknowledged that:

“… in the modern age, the distribution of information across national borders via telecommunications lines has become extremely easy. If a program, etc. is transmitted from outside the territory of Japan via a telecommunications line and provided within the territory of Japan but the effect of a Japanese patent right does not always cover this merely because it is transmitted from outside the territory of Japan, it does not accord with the purpose of the Patent Act, which is to contribute to the development of industry through the protection and encouragement of inventions, by, among others, allowing patent holders to have the exclusive right to implement patented inventions in the course of business.”

After making such acknowledgment, the Supreme Court concluded:

“even in such cases [added by authors: i.e., in which a program, etc. is transmitted from outside the territory of Japan], there is no reason to prevent the interpretation that the effect of the Japanese patent right covers such act of transmitting when such act is, as a whole, evaluated as substantially constituting ‘provision via telecommunications lines’ within the territory of Japan.”

The Supreme Court acknowledged that, while part of the Distribution (of the Programs) had the appearance of occurring outside the territory of Japan, when viewed as a whole:

Based on the above, the Supreme Court specified the following points,※5 and concluded that FC2 and HPS had transmitted the Programs via telecommunications lines substantially within the territory of Japan through the Distribution, and that therefore the Distribution fell under “providing [services] through a telecommunication line” (Article 2(3)(i) of the Patent Act):

In addition, the Supreme Court noted that the Distribution automatically created the effects of the Display Device Inventions at terminals located in Japan, and that the circumstances relating to the location of the server and economic impact were the same as (B)(ii) and (C) above. Given this, the Supreme Court concluded that the Distribution also fell under an act of “transferring, etc.” (Article 101(i) of the Patent Act).

The plaintiff, Dwango, owned Japanese Patent No. 6526304 (“’304 Patent”) pertaining to system inventions (the “System Inventions”).※6 Dwango alleged that the systems (i.e., the network of servers and terminals, etc., which are the “Systems” described in the above <Figure: Structure of the Services>) used in providing the Services fell within the scope of the System Inventions and that the acts of one of the defendants, FC2, of transmitting files for the Services (the “Files”) from servers located in the USA to user terminals in Japan constituted an act of “producing” under Article 2(3)(i) of the Patent Act with respect to the Systems.※7

Based on these allegations, in 2019, Dwango commenced litigation against FC2 and HPS in the Tokyo District Court, seeking an injunction to prevent the transmission of the Files, as well as an award for compensatory damages.

The key issue in Dwango II was

On March 24, 2022, the Tokyo District Court dismissed the claim of Dwango, holding that the act of producing a patented product under the Patent Act occurs only when a product that meets all of the constituent elements of the patented invention is newly produced in Japan, and such had not occurred in this case.

Dwango next appealed to the IPHC and on May 26, 2023, the Grand Panel of the IPHC, partially accepting the claim of Dwango, found that FC2 had infringed ’304 Patent.※8 FC2 subsequently filed petitions to the Supreme Court for final appeal challenging the ruling of the IPHC.

On March 3, 2025, the Supreme Court dismissed the final appeal made by FC2, which resulted in the judgment of the IPHC being affirmed as the final and binding decision (the “Supreme Court Dwango II Judgment”).

As with the Supreme Court Dwango I Judgment, in Dwango II, referring to the principle of territoriality, the Supreme Court stated that a Japanese patent right is effective only within the territory of Japan. However, the Supreme Court went further and acknowledged that:

“… in the modern age, the distribution of information across national borders via telecommunications lines has become extremely easy. If a system containing server(s) and terminal(s) is built partly outside the territory of Japan via a telecommunications line or such server(s) are located outside the territory of Japan but the effect of a Japanese patent right does not always cover this and thus an act of building such system does not fall under ‘producing’ under Article 2(3)(i) of the Patent Act merely because it is partly built or set up outside the territory of Japan, it does not accord with the purpose of the Patent Act, which is to contribute to the development of industry through the protection and encouragement of inventions, by, among others, allowing patent holders to have the exclusive right to implement patented inventions in the course of business.”

After making such acknowledgment, the Supreme Court concluded:

“even in such cases [added by authors: i.e., where a system containing server(s) and terminal(s) is built partly outside the territory of Japan via a telecommunications line or such server(s) are located outside the territory of Japan], there is no reason to prevent the interpretation that the effect of the Japanese patent right covers such act of building when such act or the system built as a whole is evaluated as substantially constituting ‘producing’ within the territory of Japan.”

The Supreme Court acknowledged that, while a part of the act of making the Systems had the appearance of occurring outside the territory of Japan because the Transmissions (of HTML files and JS files, etc.) were an act of transmitting files from the Web Server which was set up outside the territory of Japan and parts of the Systems made by the Transmissions, such as the Comments-Streaming Server, were located outside the territory of Japan, but, when viewed as a whole:

Based on the above, the Supreme Court specified the following points,※9 and concluded that FC2 made the Systems via telecommunications lines substantially within the territory of Japan through the Transmissions, and that the Transmissions fell under “producing” under Article 2(3)(i) of the Patent Act:

Regarding the Supreme Court Dwango I Judgment and the Supreme Court Dwango II Judgment (collectively, the “Supreme Court Judgments”), the following three points may be considered the most noteworthy:

*1

’471 Patent is titled “display device, method of displaying comments, and programs.” The Program Inventions are claimed in claims 9 and 10 of ’471 Patent, and the Display Device Inventions in claims 1, 2, 5 and 6 of ’471 Patent. Dwango also alleged the infringement of Japanese Patent No. 4695583, titled “display device, method of displaying comments, and programs” owned by Dwango. However, this patent and the issues related to it are not discussed in this newsletter as they are not the subject of the Dwango I Supreme Court judgment.

*2

Under Article 101(i) of the Patent Act, where the patent has been granted for a product invention, an act is deemed to constitute an infringement of the patent if the act is an act of producing, transferring, etc., importing or offering to transfer, etc., in the course of trade, any item or material whose only use is to produce that patented product.

*3

Some aspects of the structure of the Services differ depending on the version or type of computer program used as well as on variations in the Services themselves, but such differences do not affect the decision and conclusions reached by the Supreme Court.

*4

For further details, please refer to NO&T IP Law Update No.1, “Judgment rendered by the Grand Panel of the Intellectual Property High Court on May 26, 2023, regarding the Principle of Territoriality” (June, 2023).

*5

The below points (A) to (C) have been listed in this newsletter article for ease of understanding. The Supreme Court judgment itself, however, does not present them in such an ordered and concise manner and different interpretations are possible.

*6

’304 Patent is titled “comment delivery system”. The System Inventions are claimed in claims 1 and 2 of ’304 Patent.

*7

Dwango also alleged that the defendant HPS jointly performed the aforementioned acts of transmission with FC2, but such allegation was dismissed early and not at issue at the Supreme Court level in Dwango II.

*8

For further details, please refer to NO&T IP Law Update No.1, “Judgment rendered by the Grand Panel of the Intellectual Property High Court on May 26, 2023, regarding the Principle of Territoriality” (June, 2023).

*9

The below points (A) to (C) have been listed in this newsletter article for ease of understanding. The Supreme Court judgment itself, however, does not present them in such an ordered and concise manner and different interpretations are possible.

This newsletter is given as general information for reference purposes only and therefore does not constitute our firm’s legal advice. Any opinion stated in this newsletter is a personal view of the author(s) and not our firm’s official view. For any specific matter or legal issue, please do not rely on this newsletter but make sure to consult a legal adviser. We would be delighted to answer your questions, if any.

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Claire Chong, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

(October 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

(September 2025)

Kenji Tosaki

Kenji Tosaki, Ryo Tonomura (Co-author)

Hoai Truong

(August 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author)

(July 2025)

Ryo Okubo, Yu Takahashi, Uchu Takehara, Naoto Obara (Co-author)

(June 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yukiko Konno, Minh Thi Cao Koike, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)

Salin Kongpakpaisarn, Pundaree Tanapathong (Co-author)

(November 2024)

Keiji Tonomura, Masaki Mizukoshi, Uchu Takehara, Hitomi Kono (Co-author)

(October 2024)

Yasushi Kudo, Tsubasa Watanabe, Hayato Maruta (Co-author)

(August 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Yoshiteru Matsuzaki (Co-author)

(April 2025)

Keiji Tonomura, Akira Komatsu (Co-author)

Poonyisa Sornchangwat, Kwanchanok Jantakram (Co-author)

Kenji Tosaki, Takahiro Hatori, Nozomi Kato (Co-author)